Humans Inspired – Chapter 1: Revolution

Crossing the border into Egypt from Israel was a huge relief. At the immigration checkpoint I met some French exchange students who had been studying Arabic in Egypt. They invited me to share the cost of an overnight van to Cairo. After about 5 minutes driving I fell dead asleep and when I woke up in the middle of the night, the driver had stopped at a halfway point to pass us off to another van. Almost no light pollution exists in the Sinai Peninsula so when I stepped outside the van into the pitch black desert, the immediate need to pee was accompanied by the most spectacular view of the Milky Way I’ve ever seen. There’s a song called Deep in the Heart of Texas that always made me think rural Texas had the brightest stars on earth but the night sky in the Sinai made me feel like I was floating in space.

When I woke up the following morning in Cairo, I was somewhat surprised to see a fully functional city. The media had portrayed it to look like a chaotic scene with failed systems, and indeed the government had just been overthrown, but the vast majority of what I could see happening in the streets seemed to be business as usual. The streets themselves reminded me a lot of Paris in the desert and I had often heard Cairo described that way. The yellow European style stone buildings all had open storefronts on the bottom floors with french style balconies above.

I had made plans via couchsurfing.com to stay with an English expat in an international section of Cairo called Maadi. Using my usual method in any new city, I hopped into a taxi and showed the driver an address written hastily on a crumpled piece of paper. When we pulled up at my host’s apartment building, I was honestly shocked to see an American-style Tex-Mex restaurant across the street. This was my first time staying in an expat neighborhood and I later found out there was a local Mexican guy from Dallas who had married an Egyptian woman there. He was now supplying a wide variety of foreigners and Egyptians alike with tacos and burritos. When I later tried the tacos, comfort food never tasted better despite how mediocre they actually were.

I’ve since learned that expats often live unresolved lives and can be rather strange. This first expat landlord proved to be both unresolved and strange. My host was an isolated and slightly bitter man who had spent his life buying and selling antiques. I came to assume he was hosting travelers as an antidote to his loneliness. The walls of his apartment were decorated with pictures of him road cycling with a group of fellow expats and the balcony had a view overlooking Cairo’s largest maximum security prison. As he went on about some jazz club in the neighborhood, I subtly interrupted him to say my purpose in Cairo was to film the revolution. He was happy to give me directions about how to find what I was looking for, but for someone who had chosen to call Egypt home, he seemed to have little to no interest in the country itself or the current ongoing political drama. It was a weird situation but he knew the city and I was given a key to my own room so I was grateful nonetheless. After getting a brief rundown of how to navigate Cairo, I went to sleep early in preparation for filming the upcoming pro-democracy demonstration in the city center.

Waking up early the following morning, I made my way with my camera and microphone to the closest metro station. It had been about 3 months since a million people had occupied Tahrir Square. They ultimately succeeded in overthrowing their government, so I was surprised that the metro was working at all. I wondered who was paying the maintenance people to upkeep the train system, or better yet, who was paying the guy driving the train. Despite no established government in Egypt, everything, including the public transportation system, seemed to be working really well. The inside of the train was packed full of people, many of whom seemed to be on their way to work. As we arrived in the underground station beneath Tahrir Square. I was even more surprised to see that only about half of the people on the train were on their way to participate in the demonstrations. Most kept going about their day as if nothing was amiss. Imagine an entire country still fully functioning in the absence of a government. This truly was a revolution.

As I got off the train and walked through the underground metro station, all I could hear were sounds of loud chanting in Arabic just aboveground. I became almost paralyzed with fear and nearly turned around. I had seen so many news stories depicting what was going on there in a dangerous and negative light. There were multiple government travel warnings posted by the US state department telling Americans not to travel to Egypt. In that moment I became aware that I really was just an inexperienced, naïve, wanna-be journalist, and I had no idea what I was getting myself into. People with Egyptian flags ran through the metro station passing me and my camera as if I didn’t exist, hastily making their way up the stairs into an increasingly loud and unknown abyss. The closer I got to the exit, the louder the chanting became and the more nervous I felt. I was truly terrified. As I emerged with them into the light of the square, I began to see men and women alongside their families smiling in good spirits, and the loud foreign chanting I was hearing began to feel more like a celebration than a protest. That’s exactly what it was.

For a twenty-four-year-old guy from Texas with little to no plan, I had shown up in Tahrir Square at a very opportune moment. It was the biggest planned demonstration in Egypt’s history. News accounts later told us there were about one and a half million people in the square that day. Representation from every walk of life had shown up for this and people seemed truly happy to be together, unified against their fallen government and celebrating the long overdue possibility of a better future. I had never seen anything like it. The fear I was feeling quickly turned into excitement and curiosity. In the background one of the main government buildings stood empty, scorched black by fires and missing windows, nearly completely destroyed by anti-government protestors a few months before. In the distance I could see a man waving a large Egyptian flag on top of an electric light pole above the massive crowd. It was a sea of red, black and white, colored by hundreds of thousands of proud demonstrators carrying their country’s flag. As an American, ideas of freedom and revolution had always existed in the back of my mind, but this was the first time I had ever seen it, smelled it, touched it. It was everything I hoped it could be, and it was finally time to put my camera to good use.

As I began walking around with my tripod open and the shotgun audio mic attached to the top of my camera, I took on the disposition of a proper freelance journalist taking action shots. The demonstrators could surely spot me a mile away because before I approached anyone on my own volition, I had a line of people taking turns to eagerly tell me about their revolution. Most of them were young, educated, and English speaking. I didn’t know enough about what questions I should be asking, so I just let them describe what was happening and why.

From what I had seen, the mainstream media in the US contained a lot of chatter about a so-called Islamic extremist group called the Muslim Brotherhood. I soon found out they were very much present in Tahrir Square. Western media spoke often about the threat of this Islamic extremist group taking control over Egypt so for me it seemed like something I should be watching out for. When I began to ask around about them, I was eventually pointed in their direction by a group of young artists calling themselves the Revolution Artists Union. As I interviewed them in their well-spoken-for spot in front of a confidently closed KFC restaurant, they told me that my interest in finding out about this media-centric topic was a waste of time.

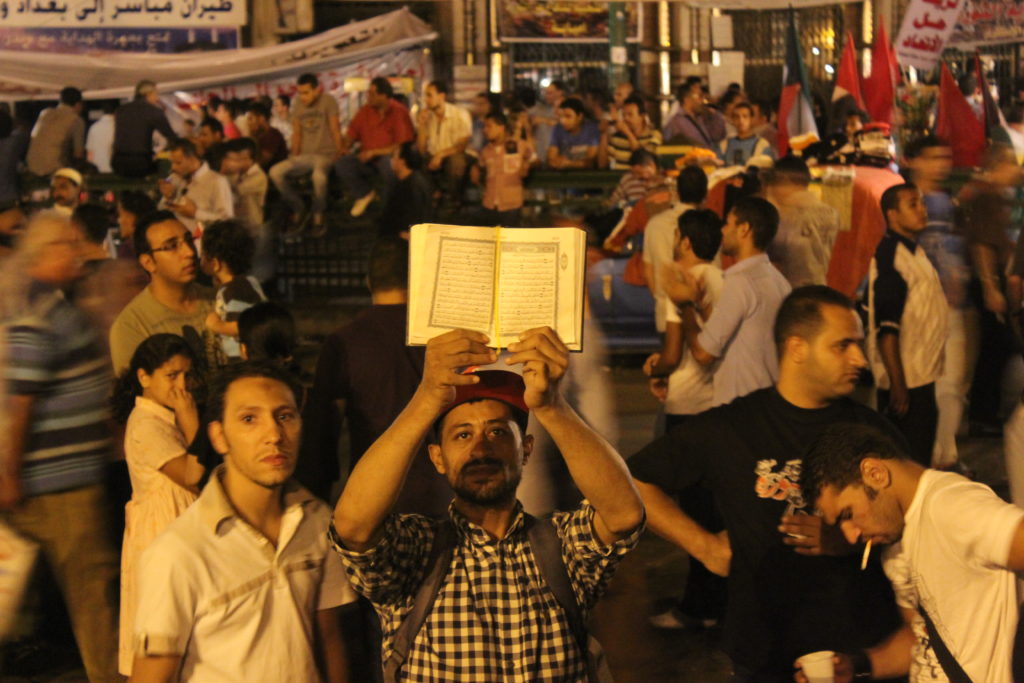

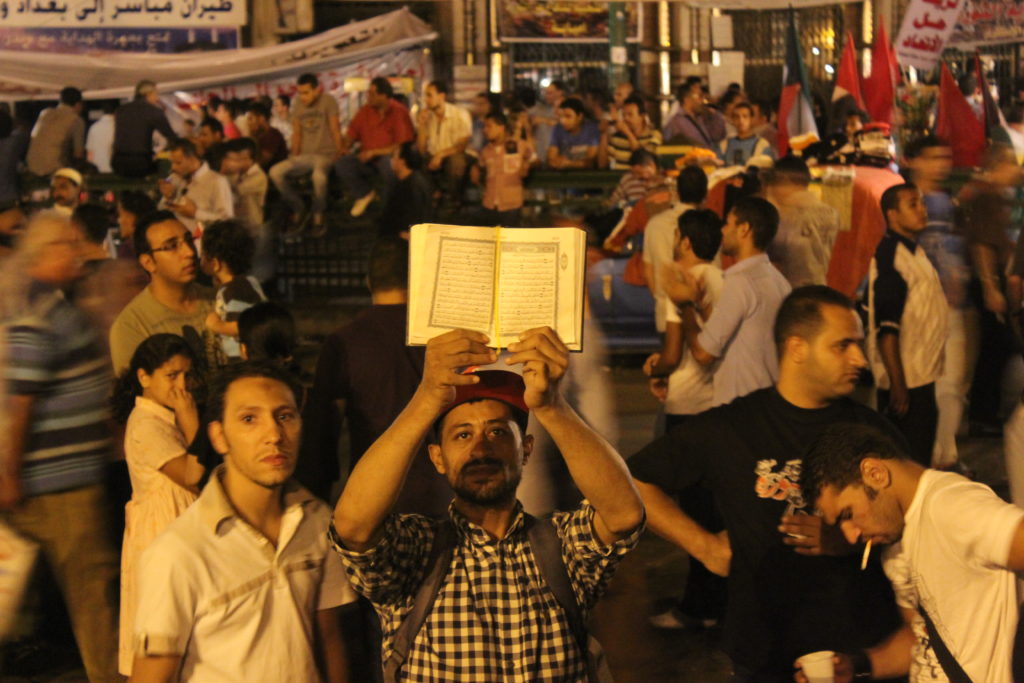

I was still curious about the Muslim Brotherhood. After spending some time with these young artists, I directed myself towards the men they had pointed out to me. As I approached, the big idea I had in my mind about them quickly shrank down to a small group of about 10 men with long beards wearing short white thobes. They were all huddled together amongst each other separate from and dwarfed by the massive crowd of inspired young Egyptians waving flags and chanting about democracy. When I saw how non-threatening these guys really were I began to relax. I talked with them for a while and they basically just wanted to show me the Quran and talk about God. This boogieman of the U.S. media was a harmless minority at best and it was obvious that the younger majority generation had a vested interest in preventing them from having any governmental power anyway.

After a few hours of walking around interviewing people and taking photos of the impressive crowd, I began to realize that I hadn’t seen anyone else walking around with a camera doing what I was doing. I thought to myself “Where the hell are the other journalists?” It was just me, my camera, and a sea of Egyptians. I soon spotted a cluster of cameras on one of the high balconies overlooking the square. I wanted to find out who they were and what they were reporting on so I made my way over to the staircase beyond the closed travel agency at the foot of the building. It was a hostel, and since, for obvious reasons, they weren’t doing business, they had begun charging journalists and media companies to use their French style balconies for reporting. As I snuck my way up to the hallway on the top floor I noticed a strong smell of cologne and thick electric cables running out of the cracked door of one of the rooms. I quietly pushed open the door. There before me was a crew from BBC Arabic doing a live broadcast.

When the BBC reporters finished recording they let me watch their footage and take a few photos of them at work. I was guessing they were Lebanese and I began to think about what their career paths must have looked like leading up to that balcony. Surely they were all working desk jobs for years before ever being out in the world experiencing this kind of action, and even now that they were, they were holed up in a hotel room talking about what was happening from a distance. I was getting a first-hand look at how the freedom to pursue what I was interested in could easily be tainted by the industrial machine the media is. Despite my efforts to date of avidly pursuing the dream of becoming a journalist, I knew that would never be me reporting from that balcony.

When night fell, I was exhausted but the demonstrators kept going. I made my way down the staircase into the metro station to catch one of the last trains of the day back to Maadi. When I woke up in expat-land the next morning, I started looking through the hundreds of photo and video files I had accumulated on my camera from the day before. Many of the photos were stunning and the video footage looked like something out of a great, professional documentary. I wanted to start editing all of it yet, I had no idea what I was going to do with any of it. Despite having recently earned a degree in Electronic Media and this mountain of fantastic footage, I didn’t know any other journalists who might have the kind of connections to make use of what I had on my hard drive. When I emailed samples of what I had accumulated to big companies like CNN and BBC they fell silent, and after a few days of not getting any response I was frustrated. When I began talking about it with my Couch Surfing host, he suggested talking to his friend from Denmark to get some ideas. Apparently his friend was a freelance print journalist working in Cairo on a story. “Couldn’t you have told me this earlier?” I thought.

His name was Henrick Byrn. We had arranged to meet at a cafe in central Cairo. There he was wearing white linen shirt sitting at a curbside table looking like the journalists I had seen portrayed in movies. Henrick was writing down his observations on a small pad of paper with an old fashioned pen, chain-smoking straight cigarettes and drinking Arabic tea. When I sat down with him he offered me a cigarette. As we sat and smoked, a million questions ran through my mind. I was down to about 1000 dollars in my bank account and the loudest questions mostly related to figuring out how to actually sell some of the media I had accumulated. He told me all about his network of print media contacts and how, contrary to publishing laws in the US, you can actually sell a single written story to as many media outlets as you want in Europe. It turned out he was writing a story about a prison break that had happened in the wake of Egypt’s fallen government and the large population of escaped prisoners now roaming the streets of Cairo. He showed me the story on his laptop and as I read it, I realized the prison he was writing about was directly across the street from where I was staying. I wondered if Cairo really was as dangerous as he made it sound in his story. I also wondered how he could have written such a detailed story about a prison in Cairo having only been there for a couple of weeks. I began to see that the theme of his story wasn’t the prison break, but the ambiguous danger that may or may not be looming on the streets of Cairo as a result of it. Here was a guy sitting comfortably without fear at a street-side table in the middle of the city, writing a sensationalist story about how terrifying the streets of Cairo are in post-revolution Egypt.

He told me to focus on creating my network and that was helpful advice for me at the time. Henrick had translated the same story into multiple languages and sold it to a handful of crime magazines in his rolodex of media contacts throughout Europe. So far he made close to 15,000 Euros doing that. He wasn’t sitting there thinking about changing the world or telling the truth as I so wanted to believe he might have been. He was booking a flight to Indonesia to go sailing with a friend on the money he just made. Having money and going sailing sounded great but I couldn’t imagine focusing my creative energy on feeding the airport magazine readers of Europe another round of fear-porn. I was interested in journalism because I wanted to share the truth. It was massively disappointing to see my ability to earn a living through journalism depended on how good I am at selling sensationalist content to people willing to publish it. This was the first time I knew I didn’t want to be a journalist.

After meeting Henrick, I decided to take a minute away from my pipe dream journalism mission to go see the pyramids. After all, I was in Egypt and that’s what you do. The demand for tourism was virtually nonexistent at the time so when I got out of the taxi near the Great Sphinx of Giza, I was bombarded with animal merchants desperately trying to sell me camel rides and guided tours. One guy walked up to me and opened a cold glass bottle of Sunkist orange soda and put it in my hand. “A gift for you,” he said, as he proceeded to put his hand out for money. Egyptians were clever that way. If they want your money they’re not going to sell you something. They’re going to create a situation where you owe them money, already leaving you powerless at the whim of the dollar signs in their eyes. It was hot outside and the soda was refreshing, albeit a manipulative soda.

I had always thought aliens must have built the pyramids with some galactic construction equipment that could move mountains, but when I got close to them they were actually a lot smaller than I had imagined. The one and a half million people in Tahrir Square were mostly Arab Muslims, so when I found myself thinking about the Pharaohs who built the pyramids of Giza, I wondered where the hell their lineage went. Turns out the ancestral descendants of the Pharaohs are a small Coptic Christian population in Cairo who are communally focused on waste management. I’m not a historian, but it was interesting to find out the royal lineage of Egypt had become the garbage men, and with all the trash I was seeing near the Pyramids I thought to myself, “Huh, I guess that makes sense.”

Despite the garbage and money-hungry tourist hunters, the pyramids truly were a sight to see, but the urban sprawl leading up to them did not make me feel like I had left the city, so I decided to take a train to Alexandria. When I got to the train station there was a chaotic crowd of mostly men who were competing for a position to buy tickets from the ticket office. I could see it would be impossible for me to get a ticket so I walked with my backpack to the loading platforms with hopes of buying a ticket off of someone else. The scene there was seriously difficult. I had no idea which train was which, but I knew all the train tracks were pointed toward the only other major city in Egypt, Alexandria. I decided to just jump on one of them. The train was full and I found myself standing with my backpack among other surplus passengers between the overflowing boxcars.

I was almost stuck in a state of openness and trust among strangers from the positive experiences I had in Tahrir Square. In the hot noisy space between boxcars I felt safe and relaxed enough to go in search of someone who could tell me whether or not the train was bound for Alexandria. There were two men talking amongst each other right in front of me and when I started speaking English to them I immediately felt a dark energy. They were quick to appear interested in any questions I might have in an obviously malign way. I noticed a well-dressed man with a briefcase eying the situation. He made his way over and instructed me to stay away from the men I had regretfully caught the attention of and told me I was on the right train. A few moments of chaos followed by a leap of faith followed by an intense moment of discernment eventually got me to the train station in Alexandria.

I had read the world’s oldest and most historic library was there and normally I would have researched a cheap place to stay close to it, but the hasty exit from the experience on the train getting there had me wandering the streets looking for somewhere to check in. Night had fallen and I had no sense of where I was. I also thought the seemingly dangerous men on the train might have been following me from the train station so I was feeling like I needed to take refuge somewhere quickly. I walked swiftly for about an hour looking for anything that resembled a hotel or a hostel and eventually I began to smell the ocean. Exhausted and hungry, I finally found a cheap hotel near the sea. After a long nervous moment waiting for my debit card to clear the 20 dollar payment, I received a room key. After making my way up the shattered narrow staircase, I locked the door and began to cry.

I was far from home and it was the first time I had been completely alone in a long time. Thoughts of all of the intense things I had experienced getting to that hotel room rushed through my mind as the darkness began to take me. I remembered the Palestinian man who had been stabbed by settlers in the West bank, the guns, the walls, all the desperate people who saw me as an opportunity to get some cash, the depressing capitalist world of media and journalism. Then I remembered my dog, my Mom, my first car, my first job, pretty girls in Texas, my childhood. My mind created stories about the conventional life I wasn’t living, perhaps with someone like Silvia, a girl I had always felt close to back in College. I wondered why I had come there and what the hell I was doing any of this for. On an empty stomach at the end of my rope, I wept into the night.

In the morning I pulled myself together and walked to the nearby sea wall in downtown Alexandria. There were hotels and mosques along the sea, many of which seemed to have been built in a more prosperous time. It was hot and dusty and there weren’t any tourists. In the water I saw some children swimming alongside their mother who was covered in a burka in the shallow water. I had been so hungry for so long for exotic and foreign experiences that when I found myself with no appetite for them anymore, those sights began to feel uninviting and overwhelming. As I forced myself to eat a dry bland pastry with cheese for breakfast, I knew I couldn’t stay there.

I hadn’t realized how much negative energy I had absorbed alongside what I was experiencing. I had gone past my limit. Taking the train back to Cairo was a breeze because I knew I had hit rock bottom in that hotel room and the only way to go from there was up. I had managed to get to the ticket counter in Alexandria this time so I had a window seat on the way back. As the desolate outskirts of Cairo began to appear in my window, I was starting to fantasize about traveling farther East. My friend Rami from Austin had studied abroad in China and he had told me all about how easy it was to make good money teaching English in Shanghai. About 8 months ago in the weeks before leaving Austin, I had also met a younger girl named Mary who told me she was going to visit her expat mom in Shanghai close to when I was planning to arrive there. They were planning a family trip to Fuji Rock Festival in Japan before heading to Shanghai, and she told me she had an extra ticket if I wanted to go. I had just met her, but her mom sounded cool so I decided to book my flight out of Egypt to Tokyo instead of going directly to Shanghai. I was down to about 500 dollars in my bank account so I had no idea how I was going to manage traveling in a country as expensive as Japan for two weeks, but I had made it this far so I figured it would all work out.

In the taxi on the way to the Cairo airport I thought about how different I felt from my arrival in Egypt a month ago. I had traveled there to try my hand in multimedia journalism but I was walking away with so much more. The mass media had me so fearful of Egypt that when I first arrived I thought I might naively walk into the hands of the wrong people, but from those first moments in Tahrir Square with the massive crowd onward, I was beginning to develop an immunity to darkness itself. I had transcended the fear from which I had been living my life all along while witnessing a piece of history, and I could finally let go of my desire to be a journalist in The Middle East. I was free and there was a certain mysterious quality to the road ahead that, despite my wallet getting thin, had me feeling brave again.

I had researched the cheapest ways to book all of my one-way international flights months in advance and that meant I needed to fly Etihad Airways to Japan from Cairo, a fancy Middle Eastern airline. After going through customs I was directed outside to the tarmac for boarding. When I took my seat in the coach section it felt like I was flying first class. The seats were leather and when the plane landed in Abu Dhabi for my connection to Tokyo, a colorful mist lit by LED lighting poured from behind the plastic window coverings inside the airplane for effect. It seemed like the further east I went, the more elaborate the domestic environment became, and going from Egypt to Tokyo had me feeling like I had flown into the future. The airport in Tokyo was clean and the immigration officials were warm and polite. Everything was in English alongside the Japanese writing and it was easy to navigate my way through the metro system to a hostel in the downtown area. Despite checking into the cheapest hostel I could find, I was feeling really nervous about money. I thought to myself “If I could just make it to China,” I’d start working right away and everything would be fine.

After some cheap noodles and a beer, I made the best of a jet-lagged night of sleep. When I woke up in the morning I went to find Mary, the young girl from Texas who had invited me to the Fuji Rock Festival. She had sent me a Skype message attempting to describe the train station where she and her mom had arrived in Tokyo so I jumped on the metro to go find them. After roaming the train station for about an hour I spotted a help desk with two Japanese women wearing what looked like navy blue stewardess uniforms from the 1960s. I was truly grateful for how eager these women were to actually help me find who I was looking for. They made multiple announcements over the train station loudspeaker calling out Mary’s full name and asking her to come to the help desk. Eventually that worked. After hours of being lost and alone in a sea of Japanese people, I finally met up with a familiar face.

I barely knew her, but I could see when we first met that Mary came from money. She had grown up in a wealthy part of San Antonio and when I met her in Austin she was living in a fancy house that no 20-year-old could possibly pay for themselves. She was a friend of a friend of a friend, and I had randomly ended up at a house party that she was hosting. Our mutual friend kept calling her “shipwreck” at the party and I wondered why. It turned out she had done a semester at sea on a sailboat called the SV Concordia that famously got lost out in the ocean for a number of weeks. When I told her I had sold all my stuff and was about to travel around the world, she said “You should go to Shanghai! My mom lives there and I’m going to visit her next August!” When she found out 8 months ago that I already had plans to find a job in Shanghai, she offered me a free ticket to a music festival in Japan, and now I was meeting her mom in Tokyo for the first time.

I was a jet-lagged backpacker with a five o’clock shadow ready to go to this music festival and they seemed to love it. I had just come from the revolution in Egypt which was all over the news and at that moment I had a lot going on for a 24-year-old with no money. Her mom was obviously cool living as an expat in Shanghai planning a family trip to Fuji Fest, and I got a sense that she must think the same of me as she watched her daughter wander off with me in Tokyo. Mary and I made our way back to the hostel I was staying the night before for the night, and I could tell it was her first time staying in a hostel. We planned to meet up with her mom in the morning to get a bullet train to Naeba, the ski resort town where Fuji Rock Festival takes place each year. Everything was expensive and the train was another 30 dollars I didn’t have but what could I do? These folks had been generous enough to offer to put me up in a hotel with them during the festival and I was gonna make it work.

It was my first time riding on a bullet train and I was fascinated. I loved trains as a kid and my inner child was enchanted by the quiet, technologically advanced hum of the speeding train. When I stared at the passing buildings I could tell we were going much faster than the landing speed of an airplane. Despite the distance it was a short trip, and when we got to Naeba our hotel had a hot springs pool. We were only a short walk to the music festival. All of it was beyond my imagination and, more so, my financial capacity. I was stuck halfway between running out of money in Japan and finding a job in China and I was amazed by where I had ended up.

As we made our way to Fuji Fest the following morning it started to rain, turning the festival muddy for the days to come. The recent Fukushima nuclear disaster was one of the biggest things in the news at the time and I had the thought that it could be acid rain we were walking through. Surely the government wouldn’t allow a music festival to go on like this if the radiation levels weren’t safe. That’s what I thought. With big named bands headlining and with how efficient and polite my experiences had been thus far, I found myself trusting Japan in general. During the summer the foggy forest in this part of Japan feels mystical and the whole mountain is decorated in great detail to look like some kind of fairytale for the festival. Over the course of 3 days we saw a handful of well-known bands including Mogwai, Coldplay, a Mongolian throat singing band called Hangai, Incubus, and the Chemical Brothers. During the Chemical Brothers’ set I managed to walk backstage with my camera and I got some great shots of what the laser light show looked like facing the audience. I even shook hands with the band as they came off stage.

After a little over a week in Japan I was having the time of my life, but a few days of eating delicious and expensive fairytale music festival food rendered me nearly broke. I had also ruined what was left of the shoes I had been wearing for the past 8 months in the mountain mud. I had transitioned to some cheap plastic sandals I bought in the hotel lobby. We were all planning to go to China after Fuji Fest but while Mary and her Mom were catching a flight, I had booked a cheap ticket 8 months ago on a boat from Kobe to Shanghai. When we hopped on the 30-dollar bullet train back to Tokyo, I felt relatively justified fare dodging the train conductor in the dining car bathroom. Before I went off to find my bus to Kobe, Mary’s Mom gave me a confident look as we said our goodbyes in the Tokyo train station. “See you in Shanghai,” she said.

After a three-hour bus ride to Kobe, I found myself staring at the 5-dollar hotel sandals on my feet in the port area passport control office. I really didn’t know what to expect an overnight ferry from Japan to China to be like, but when I saw that it was a very modern ship with a cafe, I honestly had my doubts they were even going to let me on without proper shoes. The rooms on the boat each had 4 bunk beds and reminded me of the many hostels I had stayed in over the past 8 months. I tossed my backpack onto my bed and went to the cafe to see if they were selling beer. While I sat sipping a can of Tsingtao I watched Japan fade away out the window and I thought about how so many immigrants must have felt coming to America by boat. Of course they probably didn’t have Teriyaki beef and beer in the cafe, much less the ability to pay the cashier with a Visa debit card. But I too was something of an immigrant cruising through the East China Sea with 100 dollars to my name and no shoes. I was on my way to the world’s newest economic superpower in search of financial opportunity.

____________________________________________________________________________________